Italy: A two-speed banking system despite the macro recovery

Italy still faces economic and political challenges, but has achieved indisputable improvements, write La Banque Postale Asset Management’s Stéphane Déo, strategist, and Stéphane Herndl, senior credit analyst, research department. But although constructive on the Italian banking sector, they note that second tier banks remain under considerable strain.

Stéphane Herndl and Stéphane Déo

What an improvement for the Italian economy since the Depression, when investors were speculating on a forthcoming IMF intervention! But the real question now is: what proportion of that improvement is purely cyclical, hence prone to deteriorate again during rainy days, and what is structural, hence resilient to a downturn.

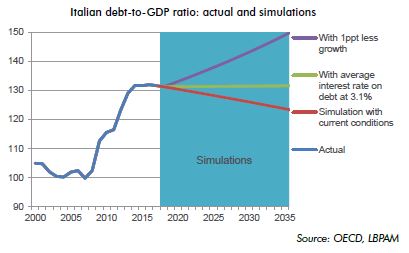

The main worry is obviously the mammoth stock of public debt, 132.0% of GDP. As far as the deficit is concerned, there’s been indeed some structural improvement, albeit hardly impressive: according to OECD estimates, the cyclically-adjusted deficit dipped from 3.3% in 2008 to 1.0% last year. This has been enough though to curb the debt-to-GDP ratio, albeit at a pedestrian pace.

So the question now is: how stable is the situation?

Most commentators fear a rise in yields which would impact the level of debt service. This sounds logical, but we find that, with the current deficit and growth, Italy can stabilize its debt-to-GDP ratio with interest rates at 3.1%, while at the time of writing the 10 year yield is at 1.8%. Note also that the duration of Italian debt has been extended. With debt-to-GDP at 132%, a 1 percentage point (ppt) increase in yields should in theory add 1.32% to debt service. But in the real world, because only a small part of the debt is rolled each year, the impact would be very slow to feed through: the debt service increases by a mere 0.08% after one year, by 0.21% after two years and only 0.35% after three.

The real issue, our model shows, is growth. Italy needs a nominal growth rate of 1.6% to make its public finances sustainable and stabilize its debt-to-GDP ratio, while the OECD’s estimate for 2017 is 1.9%. A drop in the growth rate by 1ppt would send debt-to-GDP zooming up again.

In short, public finances have improved to a point where Italy is to a large extent immune to yield moves, but definitely not to an economic downturn.

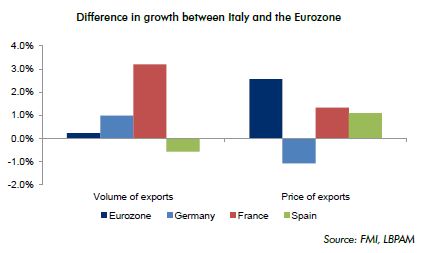

While internal imbalances, a.k.a. the public deficit, is the focus of much commentary, external balances have improved markedly, with the current account position moving from a 3.5% deficit in 2011 to almost a 3% surplus lately. This is key, as it means that Italy is repaying its external debt and does not depend on external investors. It’s a source of stability unseen for decades in Italy. What happened? Italy’s trade balance moved likewise and explains the bulk of the improvement: from a 2% deficit in 2010 to a steady 3% surplus over the past year. While there’s much debate about Italy’s competitiveness and supposedly high unit labor costs, it’s interesting to note that, since 2016, Italian export volumes have slightly outpaced those of the Eurozone by 0.2%, meanwhile the price of their exports has grown 2.6% faster over the period. This means that Italy gained market shares while increasing selling prices. That pattern is counterintuitive; it’s a sure sign that Italy has moved upmarket.

In conclusion, Italy is plagued with a number of well-known issues: low productivity growth, high unemployment rate, large and inefficient public sector, etc. However, there have been some indisputable structural improvements both in terms of internal and external imbalances.

Finally, politics adds a layer of uncertainty. The saying goes that Italian politics is entertaining but irrelevant. This time is different. We are hopeful that the German-French couple will prompt needed European reforms. However, the result of the Italian elections — with an anti-European vote possibly resulting in a Eurosceptic government — will subdue any idea of risk-sharing (consider, for example, a common European deposit guarantee, key to completing the Banking Union). This points to a binary outcome: a progressive Italian government could pave the way for more European integration and probably a further decline in risk premiums, especially sovereign spreads; while a more “anti-establishment” (for lack of better word) government could lead to a more unpleasant outcome, with markets starting to worry that the lack of a safety net for Italy during the next recession could prove very damaging. Italian politics count!

NPL tipping point

Against this backdrop, we are constructive regarding the credit standing of large Italian banks. Our view is supported by the more constructive domestic macroeconomic environment, the more robust SME and corporate sector, and the reduction of systemic risk in the banking system.

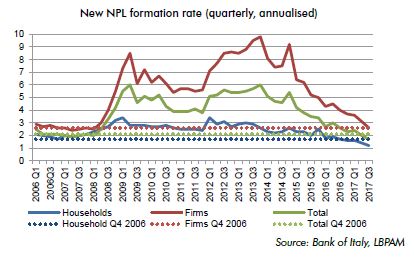

It is noteworthy that the flow of new NPLs in Italy has now reached its pre-crisis level, as recent data from the Bank of Italy highlights. This trend suggests that following a prolonged period of considerable economic stress, the Italian banking sector has now reached a tipping point. This is consistent with the aforementioned trade data hinting at the fact Italy has moved upmarket. At the micro level, it could be related to the fact that the less efficient Italian SMEs have disappeared, in a Darwinian process where only the most profitable companies survived.

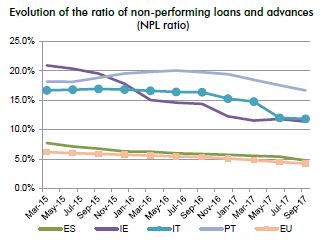

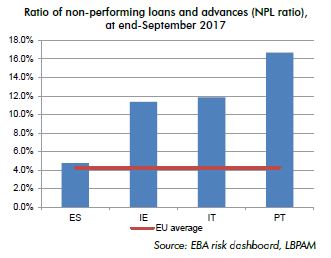

At still more than EUR260bn gross at end-2017, the stock of non-performing exposures undoubtedly remains a drag for the Italian banking system and for the broader economy, as it requires higher provisioning and hampers banks’ profitability and, ultimately, their solvency. The issue of NPLs is, however, most acute for second tier banks, whilst, in our view, large Italian banking groups appear to have put it behind them. This is because the large domestic banks could more readily absorb the impact of marking down troubled exposures — to the considerably lower level at which distressed loans are currently sold in Italy — owing to their more diverse, higher profitability and their superior access to equity capital markets. The measures put forth by the Italian government to shore up troubled banks have also helped stabilize the sector and we now assess that the systemic risk linked to the Italian banking sector has materially receded.

By contrast, second tier Italian banks show weaker profitability and average levels of provisioning. This stress is compounded by the more limited leeway for the Italian government to provide support to its banking system under the EU State Aid framework last updated in 2014 and stretched public finances, which prevent the Italian government from providing broad support comparable to what Spain or Ireland did with SAREB and NAMA, respectively. More recently, the European Single Supervisory Mechanism (SSM) has also added pressure on the Italian banking sector, as it is keen to see banks boost their coverage of troubled exposures to render the European banking system more resilient to future financial crises.

Taken together, these factors explain why second tier Italian banks remain under considerable strain which will offset the benefit of the improving domestic macro environment. It may also press them into consolidation, which we would see as a positive credit development for the sector.